It’s tempting to think our memory works like the memory of a video recorder, in that it replays information exactly as recorded. This isn’t always the case.

Based on how memories are stored and retrieved, they’re prone to errors called memory distortions. A distorted memory is a memory whose recall differs from what was encoded (recorded).

In other words, our memories can be imperfect or even false. This article will discuss how we store and retrieve memories. Understanding this is key to understanding how memory distortions occur.

How we store memories

In a previous article about the different types of memory, I pointed out that information in long-term memory is stored mainly as ‘pieces’ of meaning. When we talk of memory distortions, we’re mainly concerned with long-term memory. Things registered in short-term memory are often easily and accurately recalled.

The best way to understand how we store memories is to think of your long-term memory as a library, your conscious mind being the librarian.

When you want to commit something new to memory, you have to pay attention to it. This is akin to a librarian adding a new book to their collection. The new book is the new memory.

Of course, the librarian can’t just throw the new book onto a heap of randomly collected books. That way, it’d be difficult to locate the book when someone else wants to borrow it.

Similarly, our minds don’t just gather random memories on top of one another, with no connection to one another.

The librarian has to place the book on the right shelf in the right section so it can be retrieved easily and quickly. To do that, the librarian has to sort and order all the books in the library.

It doesn’t matter how that sorting is done- according to genres or author names or whatever. But once the sorting is done, the librarian can place this new book in its appropriate place and retrieve it easily and quickly when needed.

Something similar happens in our minds. The mind sorts and organizes information based on visual, auditory, and mainly, semantic similarity. This means a memory is stored in your mind in its own shelf of shared meaning, structure, and context. Other memories on the same shelf are similar in meaning, structure, and context to this memory.

When your mind needs to retrieve the memory, it simply goes to this shelf instead of scanning every memory on every shelf in the library of your mind.

Retrieval cues and recall

A student enters the library and asks the librarian for a book. The librarian goes to the right shelf to fetch the book. The student cued the librarian to bring the book.

Similarly, external stimuli from the environment and internal stimuli from the body cue our minds to retrieve memories.

For example, when you go through your high school yearbook, the faces of your classmates (external stimuli) make you recall their memories. When you’re feeling depressed (internal stimuli), you recall times you felt depressed in the past.

These internal and external cues are called retrieval cues. They trigger the appropriate memory pathway, enabling you to recall the memory.

Recognition versus Recall

You may recognize a memory, but you may not be able to recall it. Such a memory is called metamemory. The best example is the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon. You’re confident you know something but just can’t seem to access it. Here, your retrieval cue activated the memory but couldn’t recall it.

The librarian knows the book you requested is in the library, but they just can’t pinpoint on which shelf or in which section of the room. So they search and search, sifting through books, just as you search and search for the hidden memory in the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon.

This raises the all-important question: What does recall depend on?

Encoding specificity principle

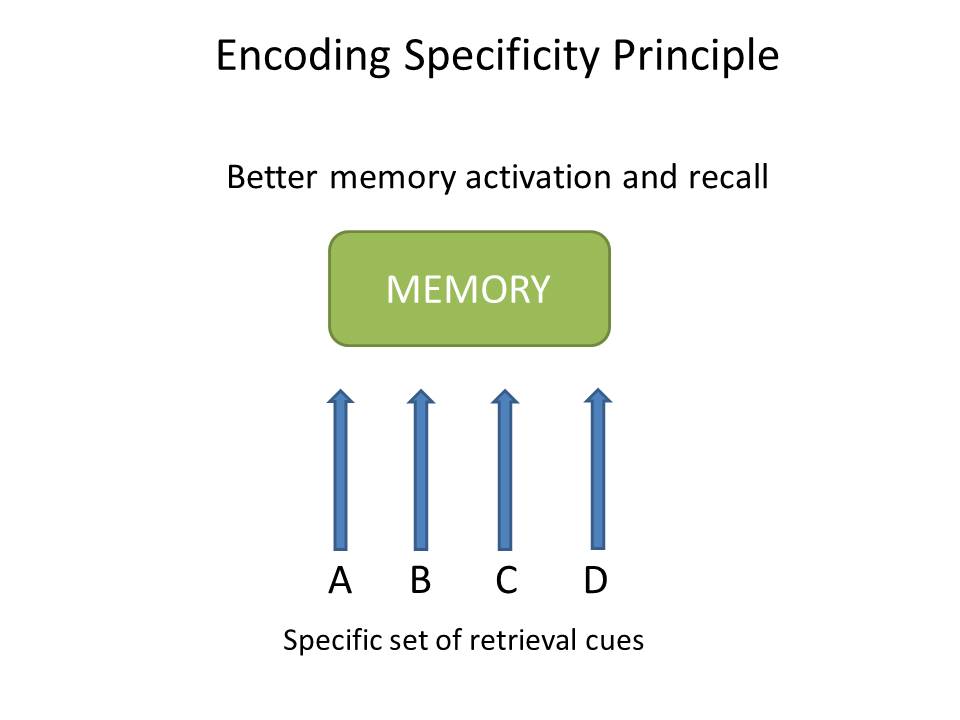

Being able to recall a memory is a game of numbers. The more retrieval cues you have, the more likely it is that you’ll activate a memory and recall it accurately.

More importantly, the specific set of environmental cues that were present when you were registering a memory has a powerful influence on recall. This is called the encoding specificity principle.

In simple words, you can better recall a memory if you’re in the same environment as the one you encoded it in. This is why dancers prefer rehearsing on the sets of their actual performance and why learning to drive using road simulators is effective.

A classic study of scuba divers showed they were better able to recall words on land that they had learned on land. For the words they learned underwater, recall was better when they were underwater.1

Such memories are called context-dependent memories. When you visit the area you grew up in and experience related memories, those are context-dependent memories. They’re triggered solely because of the environment you’re in. The retrieval cues are all still there.

In contrast, state-dependent memories are triggered by your physiological state. For example, being in a bad mood makes you remember the times you were in a bad mood previously.

The above picture explains why cramming is a bad idea when you’re memorizing for exams. In cramming, you register a lot of information in your memory in a short period. This makes fewer cues available for you to use. You begin memorizing in a particular environment with cues A, B, C, and D. These limited cues can only help you remember so much.

Spaced learning, where you memorize stuff by dividing it into manageable chunks over time, allows you to make use of more sets of specific cues.

You learn some stuff in an environment with cues A, B, C, and D. Then some more stuff in a new environment with cues, say C, D, E, and F. This way, having more retrieval cues at your disposal helps you memorize more.

Besides the cues available during encoding, recall also depends on how deeply you process information during encoding. Deeply processing information means understanding it and aligning it with your pre-existing knowledge structures.

Schemas and memory distortions

Schemas are your pre-existing knowledge structures formed by past experiences. They’re primarily what give rise to memory distortions. Let’s head back to our library analogy.

Just as the librarian organizes books in shelves and racks, our minds organize memories in schemas. Think of a schema as a mental shelf containing a collection of associated memories.

When you memorize something new, you don’t do it in a vacuum. You do it in the context of the things you already know. Complex learning builds on simple learning.

When you try to learn something new, the mind decides on what shelf or schema this new information will reside. This is why memories are said to have a constructive nature. When you learn something new, you’re constructing the memory from the new information and your pre-existing schemas.

Schemas not only help us organize memories, but they also forge our expectations of how the world will work. They’re a template we use to make decisions, form judgments, and learn new things.

Schema intrusions

If we have certain expectations of the world, they not only affect our judgments but also taint how we remember things. Compared to individual pieces of memory, schemas are easier to recall. The librarian may not know where a specific book is, but they probably know where the section or the shelf for the book is.

In times of difficulty or uncertainty, we’re likely to rely on schemas for recalling information. This can lead to memory distortions called schema intrusions.

A group of students was shown an image of an old man helping a younger man cross the street. When they were asked to recall what they saw, most of them said they saw a young man helping an old man.

If you didn’t immediately realize their answer was wrong, you just committed the same error as they did. You, and those students, have a schema that says “younger people help older people to cross streets” because this is what usually happens in the world.

This is an example of schema intrusion. Their pre-existing schema intruded or interfered with their actual memory.

It’s like you saying an author’s name to the librarian and they immediately rushing to the author’s section and pulling out a best-seller. When you explain that’s not the book you wanted, they look confused and surprised. The book you wanted was not in their schema of “what people usually buy from this author”.

Had the librarian waited for you to mention the name of the book, the error wouldn’t have occurred. Similarly, we can minimize schema intrusions by collecting complete information and trying to process it deeply. Simply saying “I don’t remember” when we’re not sure about our memory helps too.

Misinformation effect

The misinformation effect occurs when exposure to misleading information causes us to distort our memory of an event. It stems from under-reliance on one’s own memory and over-reliance on the information others provide.

Participants in a study witnessed an accident involving two cars. One group was asked something like “How fast was the car going when it hit the other car?” The other group was asked, “How fast was the car going when it smashed the other car?”

Participants in the second group recalled higher speeds.2

Mere use of the word ‘smashed’ distorted their memory of how fast the car was actually moving.

This was just one event, but the same technique can be used to distort an episodic memory comprising a sequence of events.

Say you have a vague childhood memory and haven’t been able to connect the dots. All someone has to do is fill in the gaps with wrong information to implant a distorted memory in your mind.

The false information makes sense and fits well with what you already know, so you’re likely to believe and remember it.

Imagination effect

Believe it or not, if you imagine something repeatedly, it may become a part of your memory.3

Most of us have no trouble segregating imagination from real-world memories. But highly imaginative people may be susceptible to confusing their imaginations with memory.

It’s not surprising because the mind generates physiological responses to imagined scenarios. Imagining smelling your favourite food may activate your salivary glands, for example. This indicates that the mind, at least the subconscious mind, perceives the imagined as real.

The fact that many of our dreams are registered in our long-term memory doesn’t make confusing imagination with memory all that surprising either.

The key thing to remember about false and distorted memories is that they may feel exactly like real memories. They can be as vivid and seem as accurate as actual memories. Having a vivid memory about something doesn’t necessarily mean it’s true.

References

- Godden, D. R., & Baddeley, A. D. (1975). Context‐dependent memory in two natural environments: On land and underwater. British Journal of psychology, 66(3), 325-331.

- Loftus, E. F., Miller, D. G., & Burns, H. J. (1978). Semantic integration of verbal information into a visual memory. Journal of experimental psychology: Human learning and memory, 4(1), 19.

- Schacter, D. L., Guerin, S. A., & Jacques, P. L. S. (2011). Memory distortion: An adaptive perspective. Trends in cognitive sciences, 15(10), 467-474.