It’s common to see two people getting stuck in an argument where one of them says something like:

“Answer my question! You’re deflecting!”

When humans ask questions, they expect a straightforward answer. They don’t want you beating around the bush because it means extra and unnecessary cognitive processing. While some can handle the meandering, others with low patience may find it hard to tolerate.

When arguments occur, the questions usually aren’t just questions. They’re often accusations. And when you accuse someone of something, they feel compelled to defend themselves because that’s what humans do. That’s where deflection comes in. It’s a way to defend against a perceived accusation.

Deflection can be defined as a defense mechanism often used to avoid the emotional pain brought on by the costs of being accused of wrongdoing.

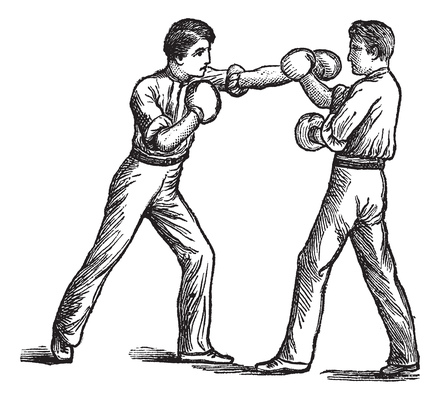

Just as you might deflect a punch with your arm to protect yourself physically, you can protect yourself emotionally from an ’emotional punch’ with psychological deflection.

The costs of being accused of a bad thing are primarily social. Your credibility, likability, and image suffer when you get accused of something bad, whether you did it or not. It makes sense to avoid such costs with deflection.1Bitterly, T. B., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2020). The economic and interpersonal consequences of deflecting direct questions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(5), 945.

“Stop deflecting!”

Before we dive into the colorful ways people deflect in arguments, I want to highlight an important point. Just because you can sense deflection is happening doesn’t always mean it is. Say you accuse someone of something wrong. Instead of responding to your accusation directly as you’d like, they talk about something unrelated.

It’s easy to jump to the conclusion that they’re deflecting. We tend to get aggressive when we accuse someone and are less likely to tolerate beating around the bush. But the accused might be beating around the bush because your accusation requires that. Not all questions can be answered straightforwardly.

Whether someone is deflecting or not is purely based on their intentions. Unfortunately, we can’t figure out others’ intentions easily. We can only assume them based on what we’re seeing. Before ascribing bad intentions to someone, it’s always good to double and triple-check your assumptions.

The deflector will eventually give themselves away if you remain rational and facts-oriented. They’ll run out of deflections.

Types of deflection

1. Changing the subject

Classic deflection. You accuse someone of X, and they change the topic to Y to avoid responding to X. This deflection tactic is easy to catch. If you do catch it, the accused might magnify the importance and priority of Y over X.

Anne: “I can’t believe you said those hurtful things to me at the party.”

Tim: “I have to fix the leak in the water tank. That’s more important right now.”

It doesn’t matter whether or not Tim is right. They might both agree that addressing the water tank issue is more critical right now. The point is that Anne’s raised issue (X) was ignored in favor of Tim’s concern (Y).

Deflection is more challenging to detect when the accused reasonably explains their deflection, as Tim did. That doesn’t mean they were not deflecting. Maybe Tim didn’t want to address Anne’s issues. Maybe the water tank thing could wait. Tim knows in his mind whether he deflected, reasonably or not.

Deflection is easy to detect when someone gives an unreasonable explanation for changing the subject. Had Tim said: “Can we talk about this later? I want to check my email.” This would more likely come across as deflection. It’s unlikely that checking email is more important than Anne’s issue. Emails can wait most of the time. If Tim dishonestly added “It’s urgent” to his explanation, his deflection would become more reasonable and challenging to detect.

2. Asking a question

Having to defend yourself when you’re accused is an uncomfortable position to be in. So, some deflectors will shift the focus away from themselves by asking a question. When you ask a question, the attention is on the person who’s supposed to answer the question. The ‘audience’ is waiting for them to respond.

Previously, they were waiting for you to respond. Now, the social pressure to respond shifts from you to the person who’s supposed to answer your question.

Deflection that involves asking a question about the topic at hand is harder to detect. No one can say you veered off the subject. You stayed on the topic while still managing to deflect the accusation.

Tom: “You said you’d lose weight but haven’t lost any. Why?”

Ray: “Why do people want to lose weight so badly? It’s a billion-dollar industry.”

The deflection would have been apparent if Ray asked a question unrelated to weight loss. But now his question has everyone wondering about the weight loss obsession, shifting the focus away from the fact that he didn’t lose any weight.

A common way people use this deflection technique is called whataboutism or whataboutery. You accuse someone of X, and they shift the focus to Y by saying something like:

“What about Y?”

The underlying message is:

“Why are you accusing me of X? Look at Y. That’s just as bad as X.”

They might frame what they did as ‘lesser evil’ through their whataboutery as if that justifies the actions they were accused of.2Bowell, T. A. (2020). Whataboutisms, arguments and argumentative harm.

“What about Y? They’re worse than I am.”

Whataboutery can be directed at the accuser or any other third party.

The fact that someone is just as bad as the accused or worse doesn’t justify the latter’s evil actions. They’re expected to take responsibility for their actions. What others are doing is immaterial to the topic at hand- their wrongdoings.

You didn’t say:

“Why did you do X? No one else does this.”

You said:

“Why did you do X?”

Big difference. In the former case, their whataboutery may be legitimate. In the latter case, it isn’t. But, of course, it’s hard for humans to stay logical when they’re accused. To be logical in answering a question, the answer must be proportional to the question. Nothing more, nothing less.

3. Too economical

As mentioned earlier, people appreciate direct answers to their questions with economical use of words. However, if the accused gets too economical with their words to the point that their answer is too short relative to the question asked, it signals deflection. They’re trying to evade the argument by cutting it short.

Claire: “Why are you so late? You said you’d be home by 8 pm.”

Her son: “Jesus!” *Heads to his room.*

4. Ignoring

The accused may deflect the accusation by simply ignoring it.3Gillespie, A. (2020). Disruption, self-presentation, and defensive tactics at the threshold of learning. Review of General Psychology, 24(4), 382-396. It’s difficult to pull off, especially if the accuser is a close friend or relative of the accused. If a person raises an issue, it automatically means it’s important to them. If the other person ignores the problem, they invalidate the accuser’s feelings. People don’t want to risk invalidating the feelings of those they care about.

5. Denial

Often, the accuser doesn’t have enough proof to incriminate the accused. The accused takes advantage of this and denies the accusation. They know the accusation can’t be proven.

However, simply denying the accusation doesn’t work. It’s clearly deflection. The accused has to come up with a reasonable explanation for the denial. The explanation must be satisfying to the accuser for the deflection to work. This technique requires some cleverness to pull off. The accused has to think of a plausible alternate explanation for why they did what they did.

Some crafty deflectors will use ‘plausible deniability’ in their arguments. They’ll avoid taking a strong position on a topic because such a position can be easily refuted.4Walton, D. (1996). Plausible deniability and evasion of burden of proof. Argumentation, 10(1), 47-58. So, they’ll deliberately take a vague and weak position. If accused, they can change the meaning of what they say as it suits them because what they say can have multiple interpretations.

Tina: “I don’t argue with fools.”

Bob: “Are you calling me a fool?”

Tina: “I never said that.”

Given the context of this conversation, it may be obvious that Tina implied that Bob was a fool. But because she didn’t explicitly say that, she can deny her implication.

6. Turning it into a joke

Accusations are often made in a serious tone. This puts social pressure on the accused to respond. One way in which the accused delegitimizes the accusation is by saying things like:

“You must be joking.”

“You’re being serious right now?”

The goal is to convince the accuser and the audience that the accusation is so preposterous that it could only be made in the context of humor. The accused could never do anything like that. Of course, the accuser can respond by saying:

“I’m not kidding.”

But by now the deflection has worked and the focus has shifted. The accused has put the accuser in a defensive position. The reverse of this is when the accused turns his wrongdoing into a joke by saying:

“I was just joking.”

This is a common deflection tactic to mend a situation where the accused has offended someone.

7. Aggression

The accused’s defensiveness is usually in proportion to the accuser’s aggression level. If the accuser approaches the accused calmly and accuses them in a polite tone, the accused is less likely to get defensive. If the accuser is aggressive, then the accused’s counter-aggression becomes justified.

Both aggression and counter-aggression can be deflection tactics because they shift the focus on aggression vs. the topic or problem at hand.

Nathan: “How dare you break the windows of my car?”

Peter: “How dare you come here and talk to me like that?”

The focus has shifted from broken car windows to the mutual aggression. If Nathan had calmly and assertively accused Peter, the latter wouldn’t have been able to use the counter-aggression deflection tactic.

Aggression is a common deflection tactic in narcissists. When you confront them, they’ll confront you back, often aggressively. They’ll ignore the main issue and pick anything you say with a hint of aggression and magnify it. You are sure they wouldn’t have made an issue out of it in another context. They did this time to defend themselves aggressively and re-gain power and control.

8. Blame-shifting

In this tactic, the accused counter-accuses the accuser of the same thing the accuser is accusing them of.

Ravi: “Why did you misplace the documents?”

Vicky: “You misplaced them.”

Vicky probably did misplaced them, but he has nothing to say in his defense. As a last resort, he uses the blame-shifting deflection technique. This is probably the most immature deflection strategy often observed in children. Adults are unlikely to take it seriously.

Another version of this tactic is blaming an external factor for your shortcomings when you should be the one taking responsibility.

Teacher: “Why are your grades so low this semester?”

Karl: “Because you’re a bad teacher.”

Note that there’s a chance that Karl is speaking the truth when he says the teacher is terrible. If Karl really thought the teacher was more responsible for his failure, this is not deflection. He has to believe that he failed mainly because of himself for it to be deflection.

9. Identity deflection

Say you accuse someone of lying. They get angry and say:

“I’m not a liar!”

While this may not seem like a deflection tactic, it often is. Just because you accused someone of lying doesn’t mean you’re calling them a liar. Calling someone a liar means they lie most of the time. This person may not have lied to you before. When you accused them of lying, you accused them for this particular instance.

They took your specific accusation and turned it global. They made it look like you committed an act of aggression by blaming their entire personality and identity.5Thoits, P. A. (2016). “I’m Not Mentally Ill” identity deflection as a form of stigma resistance. Journal of health and social behavior, 57(2), 135-151. You didn’t. They’re doing this to deflect and shift the focus to aggression.

Note: It's possible that they are using their identity of not being a liar to prove to you that they didn't lie. It's a weak defense. Just because someone hasn't done something in the past doesn't mean they can't do it now. If they didn't lie, they have to come up with a better defense.

10. Opinionizing

It’s the deflection tactic where you say something to someone they’re not comfortable hearing, and they say:

“That’s just your opinion.”

The goal of this tactic is to minimize the value of what you’re saying so that they minimize the discomfort it causes them.6Hample, D., Benoit, P. J., Houston, J., Purifoy, G., VanHyfte, V., & Wardwell, C. (1999). Naive theories of argument: Avoiding interpersonal arguments or cutting them short. Argumentation and Advocacy, 35(3), 130-139. Opinions are less credible than facts. But there’s something called a well-formed opinion. If your opinion is well-formed, they can’t deflect it by saying it’s just your opinion. They have to come up with good reasons why your opinion is wrong.