| Aspect | Sociopath | Psychopath |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | More likely to be shaped by environment (e.g., trauma, abuse) | More strongly linked to genetics, brain abnormalities, and early developmental issues |

| Diagnosis | Informal term often used interchangeably with ASPD | Set of traits, not a formal DSM diagnosis; assessed using Hare Psychopathy Checklist |

| Emotional Reactivity | High emotional reactivity, prone to rage and impulsivity | Low emotional reactivity, emotionally detached and cold |

| Empathy | May possess limited or shallow empathy, especially toward close relations | Profound lack of empathy; unable to feel or understand others’ distress |

| Remorse or Guilt | May feel shallow remorse and guilt | No remorse or guilt; may feign these emotions convincingly |

| Conscience | Has a weak conscience and may rationalize wrong actions | Lacks conscience entirely |

| Behavior Control | Poor control; behavior is erratic, reactive, and impulsive | Better behavioral control; actions are calculated and deliberate |

| Manipulation | May manipulate impulsively and emotionally | Skilled, calculated manipulation; often charming and deceitful |

| Criminal Behavior | Crimes are typically spontaneous and unplanned | Crimes are premeditated and strategic to avoid detection |

| Violence | More openly aggressive and violent | Violence is more calculated, sometimes sadistic |

| Social Norms | Openly disregard social rules and norms | Can follow norms to mask true intentions |

| Work and Family Life | Unable to maintain stable work or family life | May maintain a façade of normalcy in work and personal life |

| Relationships | May form emotional attachments, though often unstable | Incapable of genuine emotional bonds; relationships are shallow and used for personal gain |

| Emotional Expression | Emotional outbursts and mood swings are common | Emotions are shallow, faked, or entirely absent |

| Awareness of Wrongdoing | Aware actions are wrong but may justify them | Often does not see their behavior as wrong |

| Response to Consequences | May react violently or emotionally to being confronted | Cold and composed under pressure; rarely emotionally affected |

| Charm | May lack charm or be socially awkward | Often superficially charming and charismatic |

| Motivation | May act out of emotional need, rage, or revenge | Often driven by power, control, or personal gain |

| Perception of Others | May see others as adversaries or enemies | May view self as superior or heroic; others as tools |

| Learning from Punishment | May react emotionally but fail to adjust behavior | Rarely learn from punishment; low response to fear or consequences |

| Lying and Deceit | Pathological lying to manipulate or escape | Compulsive, strategic lying to manipulate and control |

| Emotional Pain | May experience personal distress or comorbid mood disorders | May feel loneliness but rarely emotional pain tied to empathy |

| Developmental Background | Often come from chaotic or abusive homes | Often from early environments of neglect or poor supervision, with biological predisposition |

| Perception of Morality | Understand moral wrong but choose to defy it | Can intellectually discern right/wrong but feel no moral compulsion |

| Types of Crimes | Disorganized, chaotic, easily caught | Organized, stealthy, often evade detection |

| Self-Perception | May see themselves as victims or rebels | Grandiose sense of self-worth; see themselves as superior |

| Attachment Style | May attach to select individuals or groups, albeit dysfunctionally | Generally incapable of attachment, even to family |

| Societal Functioning | Chaotic and dramatic lifestyle; often jobless or unstable employment | Often high-functioning in society; may hold jobs, have families as a cover |

| Thrill-Seeking | Takes unnecessary risks impulsively | Seeks stimulation to escape boredom; takes calculated risks |

| Moral Rationalization | Justifies harmful behavior internally | Believes actions are justified and lacks any internal moral questioning |

| Reputation Management | Less concerned with appearances or how others see them | Carefully maintains a socially acceptable façade |

| Comorbidity | Frequently co-occurs with mood or personality disorders | May overlap with narcissistic or sadistic traits |

| Primary Temperament | “Hot-headed” – quick temper, erratic behavior | “Cold-hearted” – calculating, emotionless |

| Risk Awareness | Often unaware or indifferent to consequences | Fully aware but indifferent to moral/legal consequences |

| Change | May change later on in life | Psychopathy remains stable across lifetime |

Related: Sociopath vs Psychopath test

Sociopath: Definition and meaning

A sociopath, also called a secondary psychopath, is someone with Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD). They’re likely to engage in antisocial acts where they harm others. Their aggression is both reactive and instrumental. Reactive aggression is aggression due to an emotional reaction, such as anger. Instrumental aggression is harming others for selfish gain.

Sociopaths tend to disregard the rules and are likely to get into trouble with the law. Their acts of aggression are largely impulsive, with an unawareness or disregard for the consequences. They’re ‘hot-headed’ individuals.

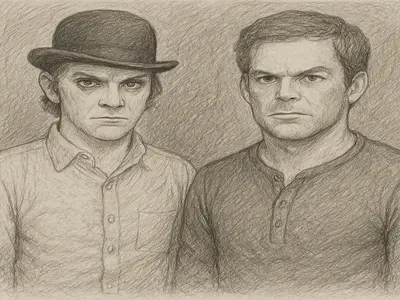

A classic example of a sociopathic character is Alex from the movie A Clockwork Orange.

Psychopath: Definition and meaning

A psychopath, or a primary psychopath, is an individual with antisocial personality who suffers from a reduced ability to experience social emotions, like:

- Remorse

- Shame

- Embarrassment

- Guilt

- Sympathy

- Empathy

- Love1Walsh, A., & Wu, H. H. (2008). Differentiating antisocial personality disorder, psychopathy, and sociopathy: Evolutionary, genetic, neurological, and sociological considerations. Criminal Justice Studies, 21(2), 135-152.

They can feel primary emotions like anger, joy, and happiness. Like sociopaths, psychopaths are also capable of both reactive and instrumental aggression. 2Khetrapal, N. (2009). The early attachment experiences are the roots of psychopathy. Interpersona: An International Journal on Personal Relationships, 3(1), 1-13. Psychopathy, however, makes one more likely to carry out premeditated, carefully planned acts of instrumental aggression.3Meloy, J. R., Book, A., Hosker-Field, A., Methot-Jones, T., & Roters, J. (2018). Social, sexual, and violent predation: Are psychopathic traits evolutionarily adaptive?. Violence and Gender, 5(3), 153-165.

Other traits associated with psychopathy include:

- Manipulation

- Lack of responsibility4Viding, E., & McCrory, E. (2019). Towards understanding atypical social affiliation in psychopathy. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(5), 437-444.

- Shallow, transient, and transactional relationships

- Lack of fear

- Promiscuity5Glenn, A. L., Kurzban, R., & Raine, A. (2011). Evolutionary theory and psychopathy. Aggression and violent behavior, 16(5), 371-380.

A good example of a psychopath is Dexter from the TV show Dexter.

Elaboration of key differences

Origin

That psychopaths are born while sociopaths are made has been a long-held belief among researchers in this area. This is the reason psychopathy was proposed to have two types: primary psychopathy (psychopathy) and secondary psychopathy (sociopathy). Primary psychopathy is strongly linked to genetic factors, whereas secondary psychopathy is strongly linked to environmental factors like poor parenting.6Lykken, D. T. (2018). Psychopathy, sociopathy, and antisocial personality disorder. Handbook of psychopathy, 23, 22.

This doesn’t mean that environmental factors have little role to play in psychopathy. A person may be born with a predisposition for psychopathy, and, given the right set of environmental triggers, they may develop psychopathy. For instance, psychopathy has been linked to maltreatment and deprivation in childhood.7Međedović, J. (2023). Psychopathy and Its Current Evolution. In Evolutionary Behavioral Ecology and Psychopathy (pp. 93-109). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. Also, the childhoods of psychopaths are characterized by insecure attachment.8Guo, F., Zhong, L., Huang, X., Chen, Z., & Sun, X. (2025). Childhood Environmental Unpredictability and Psychopathy: Mediating Roles of Insecure Attachment and Life History Strategy. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 27(2).

In contrast, sociopaths are raised by parents who fail to socialize them properly. Their poor parenting may stem from a whole host of issues like being economically disadvantaged, being too young (teenage pregnancy), or having addiction and substance abuse problems.9Walsh, A., & Wu, H. H. (2008). Differentiating antisocial personality disorder, psychopathy, and sociopathy: Evolutionary, genetic, neurological, and sociological considerations. Criminal Justice Studies, 21(2), 135-152.

Behavior control

Both sociopaths and psychopaths are highly impulsive. Since they are deceptive, their strategy inflicts significant costs on others. So, they can only benefit from their ‘cheating’ strategy if they remain undetectable. But if they stay undetectable, they’d be more successful than the average person in meeting their needs. That would increase the number of antisocial personalities in a population over time. But this is not the case. Human societies are largely cooperative.

Evolution may have given these antisocial personalities the ability to cheat, but it also gave them the curse of impulsivity. Impulsivity makes them make stupid mistakes, and they get caught. When they get caught, society creates rules and laws to handle these people and minimize their costs to society.10Miric, D., Hallet-Mathieu, A. M., & Amar, G. (2005). Etiology of antisocial personality disorder: Benefits for society from an evolutionary standpoint. Medical hypotheses, 65(4), 665-670.

Psychopaths possess the contradictory traits of premeditation and impulsivity. They may carefully plan out their sadistic crimes, but their impulsivity will make them do something stupid and get caught sooner or later. The police usually wait for these criminals to make such mistakes because it’s so common.

Compared to sociopaths, psychopaths may remain undetectable for longer.

Manipulation

Victims of antisocial personalities often get emotionally manipulated by the latter. Sociopaths, because they lack careful planning, manipulate impulsively. For example, they may put you down so that you’re begging for their approval. They put you down because they felt like putting you down. They felt animosity towards you, which made them do it. While this behavior is largely unconscious, it’s not excusable. Part of being a socially responsible individual is being aware of how your conscious and unconscious behaviors might harm others.

Psychopaths, on the other hand, manipulate in a more planned manner. They’ve probably taken the time to study you. They know which buttons to press to make you act in a certain way. They’ll often use their charm to manipulate. When confronted with their behavior, they’ll shamelessly gaslight you.

Emotional expression

Sociopaths express what they’re feeling most of the time, which is strong emotions. One of the deadliest manipulative tactics that psychopaths employ is faking emotions, especially social emotions that they’re not even capable of feeling. Psychopaths know how to express the right emotions in the right settings, even if they’re not feeling those emotions. This is done to maintain the mask of sanity and normalcy. If they didn’t do this, they’d easily get detected as abnormal.

Say you’re watching a movie with a psychopath. A gory scene comes up where a character goes through a horrible experience. You may flinch and feel bad for the character. The psychopath sitting next to you won’t even flinch or show any disgust or concern at the distress experienced by the character.

Charm

Sociopaths are anything but charming. In contrast, ‘superficial charm’ is one of the defining traits of psychopathy. They know what to say and how to say it to make others fall under their spell. They may use their charm when they’re love-bombing their victim. Psychopaths enter relationships solely for personal gain. As soon as that gain is no longer to be had, they dump the person without a second thought.11Flor, H., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Anderson, N. E., & Kiehl, K. A. (2014). Psychopathy: Developmental perspectives and their implications for treatment. Restorative neurology and neuroscience, 32(1), 103-117.